Mt. Crossan

Denali- 20,310’ June 4th, 2009

West Buttress (via Kahiltna Glacier)- Class 3-4/ Grade III

Trailhead- Kahiltna Base Camp

13.2 Miles | 13,500’ gain

Starting elevation- 7,200’ | Ending elevation- 20,320’

Kiefer Thomas, Chris Pruchnic, Colin Miller, Dan Rush, Gabe Hogan, Craig Berger

Mt. Crosson- 12,352. To gain access to Mt. Foraker (17,400’), this is the easiest route…up and over Mt. Crosson to gain the Sultana Ridge.

Crosson was named by the legendary Bradford Washburn in 1949 to honor a local, well-known bush pilot (and good friend), Joseph Crosson.

“A dream itself is but a shadow."

--Shakespeare (Hamlet)

Alaska was a dream come true. It was a bucket-list item long before I even knew I had a bucket. Because of the sheer enormity of Alaska, I felt that I needed to educate myself a bit on the state. I acquainted myself with some of the individual mountain ranges (Chugach, Alaska, Brooks) to better appreciate the differences and characteristics inherent to each one. I familiarized myself with the state atlas to understand Denali National Park and the empty spaces in between. I read antiquated accounts of old climbing epics as penned by Belmore Browne, Frederick Cook, Hudson Stuck and Bradford Washburn.

Mt. McKinley, Densmore’s Mountain, The Churchill Peaks, the ‘Middle-Aged Crisis Mountain’ etc. Denali has rightfully grown into a household name despite how one chooses to acknowledge it. The mountain serves as a one-time end-game of sorts for some, a destination to prove one’s ‘metal’ for bigger mountains of the world and occasionally, as nothing more than a tick on a list to be completed (God forbid!).

Denali is typically approached as an expedition. The logistics that go into an expedition can literally take six to ten months to plan. Even the most innocuous tangents can ruin a climb if group morale and dynamics don’t mesh. There is no equation for the professional who must turn around due to conditions vs. the novice who guides themselves to the summit in spectacular weather. I’m not saying that successful summits are a crapshoot, but even with careful planning and experience, there is like it or not, a small degree of randomness and luck. But I think this can be said of any mountain.

Denali has a vertical rise of roughly 18,000’. It boasts a whopping 20,138’ of prominence, is located only 3.5° south of the Arctic Circle and is widely regarded as one of the coldest mountains outside Antarctica. Summit success rates when all routes are factored, can go as low as 31% (1987) and as high 69% (2022). The mountain simply does not grant easy passage.

The weather on Mt. McKinley is volatile. It is subject to systems coming down from the arctic, across the Behring Strait from Russia and up from the Northern Pacific. Bad weather on Denali is the rule. The only thing that one can truly do to better one’s odds of success is to follow that one-word maxim…patience. Being subject to these three different areas (in terms of weather), storms can last for days and with the mountains’ proximity to water, snow is typically measured in feet. The winds, just like as happens with the remainder of the world’s tallest mountains, can shut down all traffic on the mountain for days.

The Kahiltna Glacier, which flows predominantly southwards is the longest in Denali National Park coming in at nearly 45 miles and is among the longest in the world. From its beginning near the summit to its terminus at 886’ above sea level, the Kahiltna ranks among the longest and largest glaciers in the world. The snow and ice taken together, covers 200 square miles. Ironically enough, it is also one of the least crevassed.

Bradford Washburn in 1937 while taking his usual cadre of aerial photos of the Alaskan Bush, photographed the now Ruth Glacier, a prominent ice flow in the southern reaches of the park. From the most current reading taken in the summer of 1992 by scientists from the Geophysical Institute of the University of Alaska- Fairbanks, was measured via sonar to see how deep the ice extended below. From the summit of nearby Mt. Dickey to the moraine bottom, the final measurement came back at almost 9,000’! This puts the actual glacier at roughly ~3,600’ thick and the Ruth Gorge as among the deepest in the world.

Denali was first spotted by George Vancouver in 1794 who reported seeing two massive, snow encrusted mountains in the distance. There was also an early Russian expedition in 1834 to the unknown peaks but little progress or information is available about this venture.

The inhabitants of the Alaskan coast and interior referred to the mountain in their own peculiar tongues and languages. In the Susitna region, the mountain was referred to as ‘Doleyka.’ Within the Alaskan interior, the mountain was known as Denali (The High One). For those living around the Cook Inlet on the southern coast, it was known as, ‘Traleika.’ The Russian people knew the mountain as, ‘Bulshaia Gora.’

In the late 1800’s, the mountain adopted the name of a local prospector and was colloquially known as, ‘Densmore’s Mountain.’ A bit romantic to be sure, but sadly it was not meant to be. Some of the interior locals living in and around Fairbanks took to naming the peak(s), ‘The Churchill Peaks.’ But even that great name wouldn’t last which, brings us to 1897 and a local gold prospector named William Dickey. William, known to be a bit charismatic, suggested a different name for the mountain. William wrote to the New York Sun, “We name our great peak Mt. McKinley, after William McKinley of Ohio, who had been nominated for the presidency, and that fact was the first news we received on our way out of that wonderful wilderness.”

For whatever reason, his name for the mountain stuck and it was henceforth referred to as such. There has always been a bit of a grassroots effort to refer to the mountain by its original, native name to pay homage and respect to the indigenous populations. But even that was only partially successful. In the end, the mountain will always bear and carry a Gemini name: McKinley and Denali.

A COLD Denali as viewed from the lower glacier.

Reflections in a fjord on the way to Seward

Traveling up the lower Kahiltna Glacier

Myself at camp-1

Group photo at the airstrip back in Talkeetna

Looking back to September of 2008, Gabe Hogan and I were at my place in Lionhead (Vail) talking about all manner of things mountainous, snowy and steep. Gabe and I were piecing together fragments of random thoughts and ideas of climbing something big and preferably, international. I knew what I wanted, but I was a little hesitant in asking. I drained my beer and watched the foam run down the glass thinking of how to say what I wanted. I looked out the window watching the ‘Cats’ groom the lower portions of ‘Born Free’ (lower ski run at Vail). I was a little apprehensive Gabe would say no to my idea.

“So, Gabe, what are your thoughts about climbing something outside of the lower 48? Say, something like McKinley.”

Gabe’s eyebrows freaked out and disappeared into his hairline. “Denali? Hell, Kiefer. That’s a serious mountain. It’s actually a dream of mine to climb it.”

“Yeah. And imagine what it would be like standing on the summit!” A smile flashed across Gabe’s face like two snails racing. “Ok. Yeah, I’m interested. But this is going to take a lot planning and training” Gabe acknowledged. “Just say the…”

Word is that a lot of people climb or at least attempt Denali by way of a guide service. I honestly felt that as much as Gabe and I had done, we didn’t need the help or assistance of a professional guiding service. Not to mention, with a guided group, one can only go as fast as the lowest common denominator. Taken as a whole, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. People can rely on and motivate one another. So, over the next few weeks, we made some calls, put out emails and did some research on guiding companies exploring this option. Considering the National Park Service issues roughly 1,200 climbing permits each season and the success rate is somewhere close to 50%, hiring a guide can be a very positive thing and even a rewarding experience, increasing one’s odds of attaining the summit and doing it safely. I think Gabe and I lacked faith in ourselves to continue pondering the idea of going unsupported. We investigated the guiding option further. We researched and talked to representatives from: Mountain Madness, AMG (Alaska Mountain Guides), Mountain Trip and AAI (Alpine Ascents International). I even forwarded an e-mail I received from Bob Covill in the CMC (Colorado Mountain Club) to Gabe from his attempt in 2007. However, in the end, even considering all that’s included in the cost and fees of going guided, neither one of us could really afford the cost of a guide. Especially since we were both basically ski bums (even in Vail, this can be attained!). I felt like someone had just sucker-punched me. So, we went back to looking at mountains within Colorado and the Pacific Northwest, only we were more melancholic about it, more subdued. There is nothing in Colorado that can hold a candle to Denali. It was a hard decision to make. Denali was dead.

Two months later, the thought of climbing Denali still hadn’t left my head. My nagging suspicion that we could do this on our own just wouldn’t dissipate. I asked if Gabe would want to meet me at Garfunkel’s one night when I got off work and talk about Alaska. “Gabe. I still can’t get Alaska out of my head. I’ve been looking at Mt. Hunter, Mt. Foraker, Ham & Eggs Route on Moose’s' Tooth…even Eskimo Pies and I keep coming back to Denali. Something just doesn’t feel right; I don’t know, kinda hard to explain. It’s the urge. Do you know what I mean?” And indeed, Gabe did. And since Gabe and I were on the same page, we knew it wasn’t the Murphy’s talking or his sneaky friend, Jameson.

“Damn, Gabe. I truly think we can do this on our own.”

Now I’m not going to sit here and say that both of us were excited and bloated with glee at this new development, we weren’t. If anything can be said, the two of us became more somber and serious. The rollercoaster anticipation of working on a dream was replaced with the grave reality of logistics and gear. We employed doubt not as an endgame but as a tool of sorts. We used it to keep ourselves grounded and not get carried away in the excitement.

This is not your typical four-hour drive, grab coffee and arrive at the trailhead for a long day kind of mountain. People lose appendages (and worse) on Denali. General statistics dictate out of 1,000 climbers, roughly 550 make the summit with 3-4 deaths. Staring at each other across the small expanse of the table, speaking only in broken sentences and half-formed words, the fifth of such meetings we had, these three aforementioned tenants now carried a gravity that we hadn’t felt before; a feeling similar to the impending dread that's felt at the onset of a poorly studied-for exam.

“We can do this. I want to do this. This can open doors to the larger mountains we both want. Let’s do this.” Gabe said in a monotone voice. Sitting on the edge of my seat staring at the beer coaster in silence and biting my lip (bad habit), I looked up at Gabe. “Ok. So, who’s coming with us?”

Gabe and I set up a meeting in Boulder at Applebee’s that consisted of Gabe and myself, Chris Pruchnic, Dan Rush, Colin Miller, Derek Wolfe, Jon Stasney and Mark Yoder. Eight people is a lot of people in one group, too many really. I turned out to be the common denominator in that, I was the only one who knew everyone else. Due to time and group commitments, work, finances and of course our families, it was expected that some of us would drop out. Derek had to back out because of work responsibilities. Mark and John also dropped out because I believe, group age dynamics. That left five people. A prime number but certainly more manageable than eight (imagine food & water requirements for eight people for three weeks!).

After securing our deposits online with the NPS in Talkeetna, we all forwarded or mailed the remainder of our permit fees to Chris (designated group treasurer). Gabe took care of air taxi service and ground transportation (Denali National Park is 238 miles north of Anchorage). I took care of accommodations in Anchorage and Chris handled our food preparations. What we found was that by dividing up the responsibilities among the members, no one particular person was overwhelmed, plus, it gave others a sense of importance in terms of usefulness and a direct stake in what was being planned. If one can have a stake in preparations, it makes the trip more…personal.

Five people however is still a prime number. It makes roped travel a less-then-ideal situation, something that should be resorted to and not initiated with. What we all wanted was that elusive sixth member. I believe none of us voiced our thoughts on this because the time was getting so close to that 30-day mark. Eventually Craig Berger became the sixth man. Colin and Gabe knew him best and their word is as good as gold. Craig goes by the name of, ‘Cheeseburgler’ on 14ers.com. Some of us just started referring to him as Cheese. What a great climbing name!

We practiced together, climbed together and e-mailed openly and truthfully to each other by way of a Yahoo Groups account that Chris had set up. When your team is spread out from Glenwood Springs to Denver to Fort Collins, any outlet for communication is crucial.

During a training session we scheduled at St. Mary’s Glacier one spring, Gabe, Colin and myself decided to get there the night before to set up camp early. We found a fairly secluded spot in the trees, set the tent up in super high winds and the three of us sandwiched into the two-man tent with beers in tow. The unfortunate and hilarious part came when Gabe threw all our beers in the tent first followed by our sleeping gear. Once we were in and settled, Gabe opened the first beer and it EXPLODED everywhere in the tent! The second beer pretty much did the same thing. Our sleeping bags were soaked, out hats and gear were wet, and it was slowly dripping beer from the ceiling. I don’t think any of us slept that night due to the winds howling outside and us howling inside! Talk about your bonding experiences!

Over the next few months, we filled in the rest of the details in regards to group practice, accommodations in Talkeetna and our climbing schedule. We were set and confirmed with six people under the expedition name, “Summit Bound”. We were set to be in Anchorage May 13th (myself a day earlier to attain a few last minute provisions and to sight-see down the Kenai) and in two days we would start our trek across the glacier looking for inspiration and ourselves.

Craig at high camp- 17,200’

The route we were planning on climbing was the West Buttress, also known as the Washburn Route in honor of Bradford Washburn who first pioneered it in 1951. Up until then, the Muldrow Glacier (north side) was the standard way in, coincidentally; both routes merit an Alaskan grade II designation (out of VI). I’ve even seen the West Buttress referred to as the Handicap Access Ramp (I like that one).

I don’t know what an Alaskan Grade II translates into in terms of Colorado mountaineering, but considering 7,200’ base camp is a world of ice, snow, hanging glaciers and crevasses, I don’t think there is a comparison.

The Washburn Route is approximately ~16.3 miles and involves roughly 13,200’ of elevation gain. 85% of the attempts on Denali are by way of this route, so isolation on the west side is a hard sell. Considering this was the first time anyone had been to the Alaskan Range, the standard route was a safe bet until we knew what to expect, although Chris and I did talk about other routes.

Chris Pruchnic at 16,080’

Permanent snowfields cover almost 75% of the mountain. The one thing I noticed almost immediately once Denali came into view from the Havilland Otter as we flew in towards Base Camp, was the abundance of hanging glaciers and seemingly non-ending bergschrunds. Since I enjoy couloir climbing back here in Colorado, I scrutinized the walls and couloirs. Alaska, at least within the Park, doesn’t have snow climbs like what’s found in Colorado. Everything is a combination of blue ice and firn. The lowly Mt. Frances (10,450’) looks just as committing and difficult as Mt. Foraker (17,400’). Mt. Hunter (14,570’) is on a level all onto its own (known as North America’s most difficult fourteen-thousand-foot peak).

We were delayed leaving Talkeetna due to weather. For two days, the skies were the color of dark pewter, threatening rain. We bided our time by becoming familiar with the small town, walking constantly and for me, reading.

During this time, I walked the cemetery a few times and studied the climber memorial located there. It’s an epitaph to those lost to the Alaskan Range (chiefly Denali National Park). I was able to locate the names of two recently deceased climbers: Karen McNeil and Sue Knott (a Vail local) who were attempting a route on Mt. Foraker called, The Infinite Spur (Alaskan Grade 6, 5.9 M5, AI4). Being from Vail, her disappearance was still fresh in the back of my mind.

We were finally cleared for departure and landed at KIA (Kahiltna International Airport- slang for base camp) on Friday May 15th. I walked over to the Base Camp Managers tent, checked in and grabbed our fuel for the next 19-20 days, seven gallons worth for six guys. It took us 2½ to 3 hours to prep everything and make ready for the glacier. We would soon know the sheer enjoyment of roped travel, although Chris (he held the Front Range Section Chair of the AAC) already knew how ‘enjoyable’ this part was.

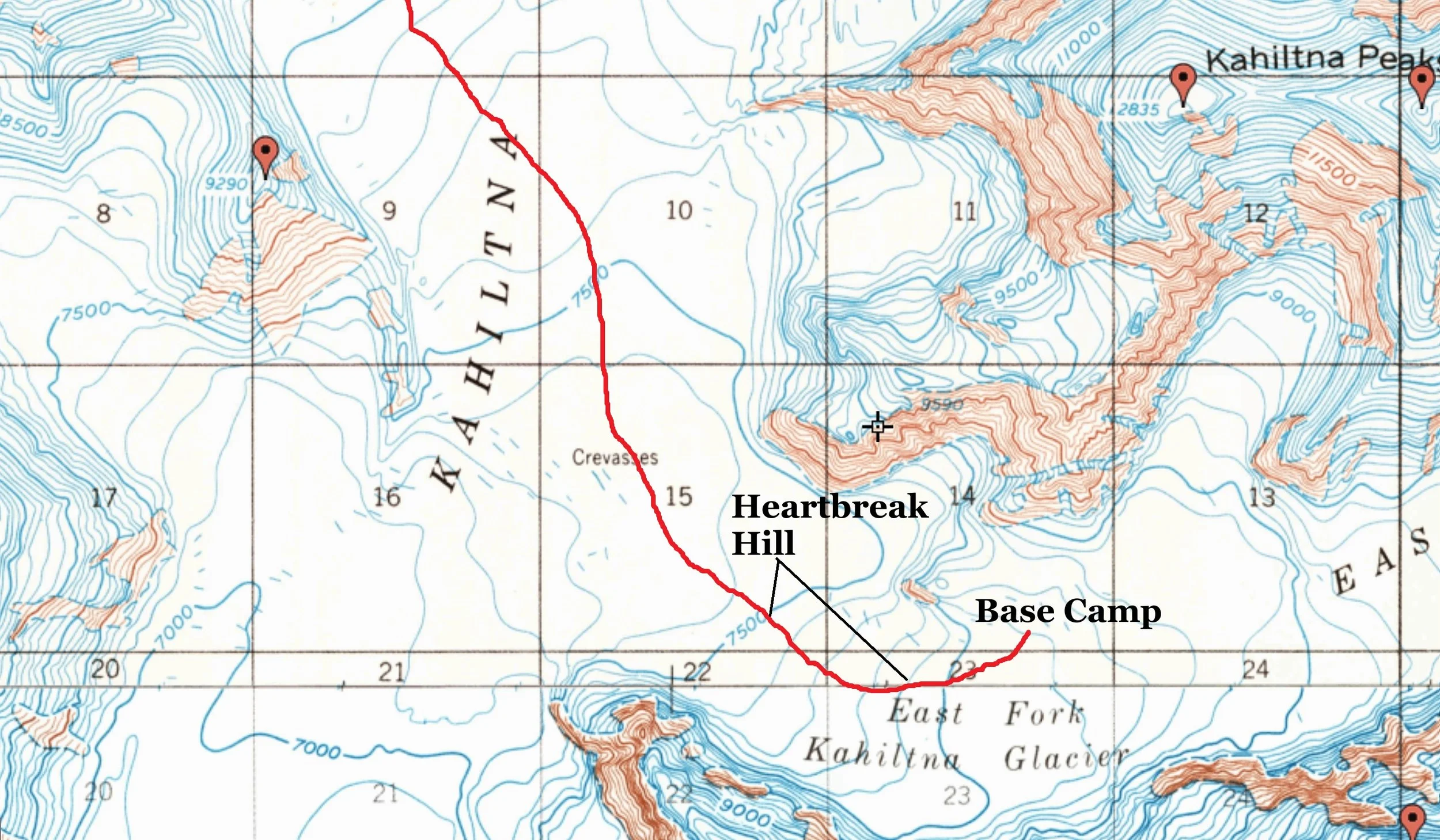

We dropped out of Base Camp and progressed down Heartbreak Hill (a well-named segment) onto the Kahiltna Glacier and followed the previous sled tracks and wands. The descent is a loss of 500’. Most people camp the first night at the Northeast Fork (Camp-1) since the increase from the low point on the glacier (6,700’) is almost 1,100’. This is done in 5.5 miles but keep in mind, you’re also carrying roughly ~65 lbs. in your pack and pulling another ~60-70 lbs. in your sled. Other than the phenomenal sights of being walled in by rock and ice, nothing about it is enjoyable. Travel is slow and tiring. Trekking across the lower Kahiltna Glacier is mostly a game of mental fortitude and stamina. It is, however, a good opportunity to focus on sled management and roped travel. But complaints aside, this is what we trained for!

We arrived at an empty site around 8:00 pm, a short way from the rest of the transients as the sun was making its slow arch below the ridges. This is where instinct took over, I’m happy to say and everyone almost immediately took to leveling tent platforms, building snow walls, prepping the stoves and setting the tents up for the night. Having years of winter camping experience is invaluable on this mountain. Knowing how to snow camp beforehand pays dividends.

Chris Pruchnic

It got cold quickly once we stopped so insulated layers came out. We had a good view up into the “Valley of Death”. Also known as the Northeast Fork, this is where routes such as the West Rib, Cassin Ridge and Reilly’s Rib originate. There were no tracks leading up into it and judging by the size and number of the crevasses, I can see why. Lisa (Basecamp Manager) had made mention that no one had ventured up into the fork due to the early openings of some of the crevasses. Denali and West Kahiltna Peak looked beyond measure. Only one other time have I felt as miniscule as I did gazing up at McKinley. That was when some buddies and I climbed Vestal Peak in the San Juan Mountains of Southern Colorado. The ‘ocean’ of peaks and troughs of the surrounding mountains seem to go on without end. Staring at the upper flanks of Denali some 9,000’ higher, I can honestly say it was intimidating and it made me question myself, ‘What the hell have you gotten yourself into Kiefer?’

We stayed up for a little while drinking hot tea and talking. We were all pretty jazzed. That whole evening felt completely surreal. But as usual, the temperatures forced a retreat to our bags and we gladly accepted our Mountain Hardwear, REI and Western Mountaineering cocoon’s, which would become our homes for the next 15 days.

I believe we all woke around 9:00 am the next morning (Saturday)…a good alpine start! And to be honest, it didn’t get much earlier than this either.

The only thing of any substance this morning was that I volunteered to throw our ‘shit-bag’ into a near-by crevasse. I tied into the rope and Gabe belayed me out to a crevasse (marked by two crossed wands). I walked out to where I could partially see down into the crack, maybe a few feet or so. I threw the bag in…waited…waited…and after a few seconds I finally heard a faint plop. I turned around and looked at Gabe. I had a HUGE excited smile on my face that said, “Get me the fuck out of here!” Yeah, that got my heart racing for a few minutes.

In addition to camp-1 being at the elbow of the Northeast Fork, it also lies at the bottom of ‘Ski Hill’. The glacier at this point starts to rise noticeably to about 10,000’ or so before leveling off again. There is one more rise of about 1,000’ to 11K-Camp, which is where a lot of people spend the next couple nights acclimating.

I had a lot of trouble negotiating Ski Hill and the side hilling that was necessary to skirt a covered but marked crevasse. My sled kept tipping over and wouldn’t stay right side up. Believe me; the language that came out of my mouth would have made Sam Kinison blush. It was brutally exhaustive work. A team of four Italians that we rode up to Talkeetna with a few days earlier passed us on this stretch. It was all I could do to keep from unleashing on one of them who decided it was easier to just ski over my rope instead of side-stepping it. I’m sure my broken Spanish would have gotten the point across. It’s a wonder there isn’t more altercations between climbers due to climbing ethics.

It wasn’t a particularly long day but physically, it was a hard one. The sleds were throwing tantrums and sled management wasn’t what it should have been. It tired us out. So, we decided to stop at 9,800’ instead of continuing on to 11K-Camp. We called it an early day, stopped and built a great campsite. This is also where the saws came out for the first time to cut and align blocks. Craig and I even found the energy to throw the Frisbee around for a while! For some reason, every night that we spent, no matter what elevation we laid our heads at, we always had a great kitchen area.

Somehow, Gabe was nominated Camp Chef. The man cooked, boiled water and organized the ‘kitchen area’ for probably close to 90% of the trip. Fact, we’re still looking into getting him a custom MSR patch that says XGK Expert. The stoves got more finicky and hard to prime the higher we went but Gabe was always on top of it. Having three stoves was a brilliant move. We ate well and out of the 15 nights we were on the mountain; I slept the best this night. No waking, no stirring, nothing; just a good, deep sleep. Two Italians or Austrians were camped just below us, and a group of six people were above us. We had good views down glacier and stellar views of Mt. Crosson and Sultana Ridge on Mt. Foraker. Dan and I witnessed the tail end of a small avalanche coming off Mt. Crosson, but certainly not the last. It was a good site that promised an easier Sunday as we trekked up to 11K-Camp.

Again, we woke when we couldn’t take the bright intensity of the sun any longer. It’s an absolute treat on a climbing trip not having to utilize alpine starts. We only used alarms a couple days. Everyone did their normal routine and since there were no crevasses where we were camped, we were forced to carry the poo-bag with us to 11K-Camp or I should say; Chris was ‘the man’ in this endeavor. But he carried one of the CMC’s (clean mountain cans), so it was fitting anyway.

A digression on wildlife that’s found on the glacier…is that there isn’t any. Any animal you might encounter remarkably got lost or was blown in by a storm or high upper winds.

As we were breaking camp Sunday morning (day 3), Chris and I discovered a dead sparrow in our rear vestibule. The poor bird had frozen to death overnight. According to park officials, what happens is that Sparrows and Finches get blown into the Central Alaskan Range and due to the sheer energy expenditure of staying aloft with no food on the upper mountain, the birds become trapped. Because of this, they have little to no fear of humans. It’s not uncommon to be stopped either on the trail or at camp and have these little guys hopping around & investigating your sled and pack looking for food. It’s sad. Our dead little friend was probably doing just this and found an alcove to take shelter. But ultimately, the bird succumbed to the temperatures. Ravens are the only bird that can fly in and out, cruising on the high ripples of wind. This was the coldest morning that we recorded. When we woke, Craig had reported that it was -13°. We broke camp and moved slowly up to 11K-Camp. This short segment only took us three hours.

Descending the Autobahn at ‘dusk.’ -Around 11:00 pm

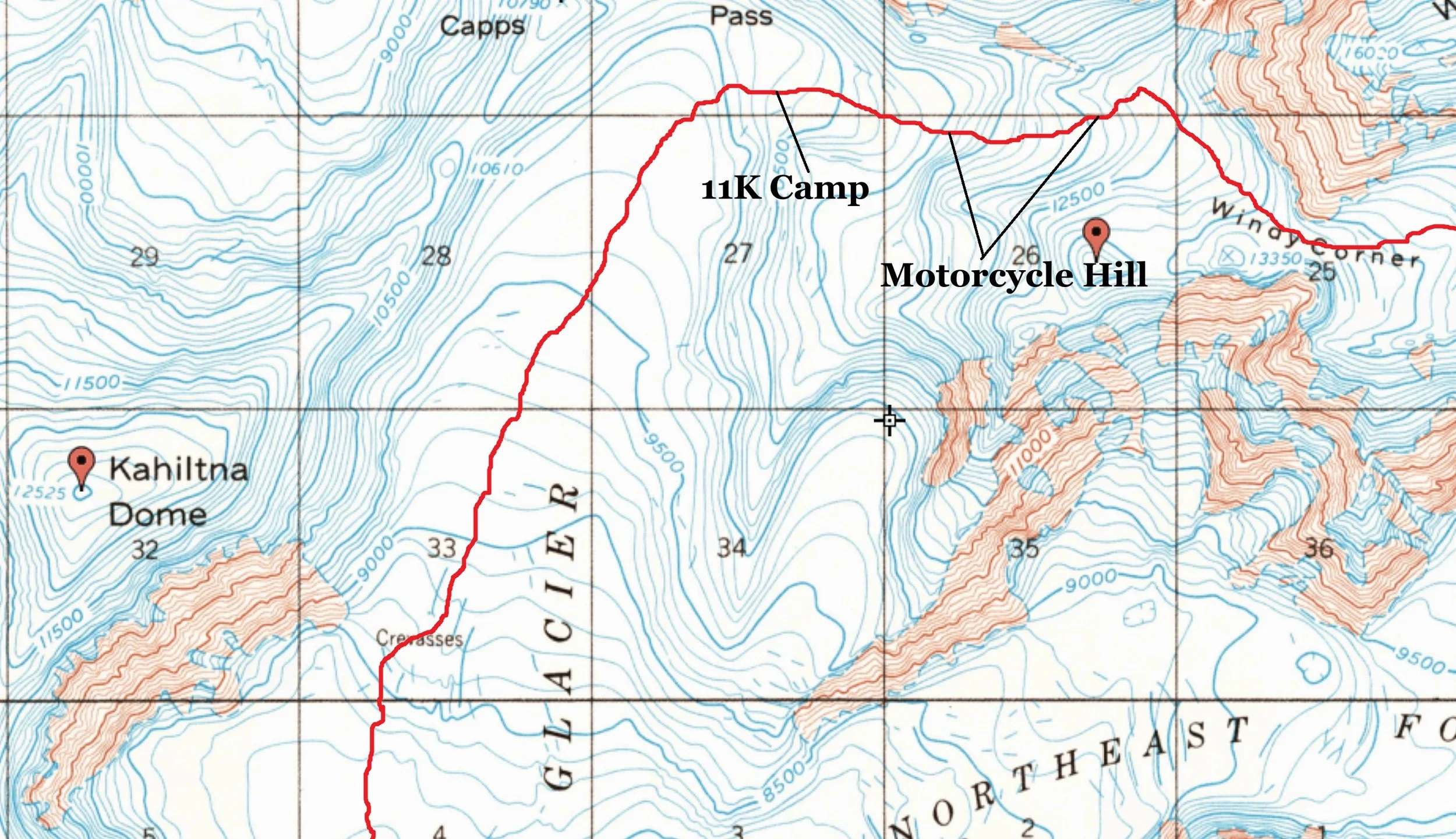

11K-Camp was amazing. It was buzzing with people from every corner of the world. Even though not everyone spoke English, everyone was linked in that we all shared a common goal. The place was a virtual town. The main thoroughfare runs straight through the encampment towards Motorcycle Hill and a confusing network of alleys and side streets radiate outward like that of a small Turkish village. Colin & Dan took to unpacking and everyone else started to dig out and improve the old tent site we moved into, like six hermit crabs.

The site of 11K-Camp sits in a small basin protected by Motorcycle Hill to the northeast and a huge slope directly northwest. Upon arrival, this slope was entirely snow covered. I made a remark to Chris that it looked like it would make for a fine snow climb save for the huge bergschrund directly at the fall line. The winds throughout the night dusted off the new powder and revealed mottled ice underneath. This ice fall was the trailing edge of a small glacier that originated up above near a feature called, ‘Windy Corner’. I remember reading about a route that ascended this wall called the ‘Trans-Canada.’ The thing was almost 50% ice and 50% snow. It was amazing and menacing at the same time.

11K-Camp was a good place. And it seemed like a good spot to introduce to everyone our hidden 7th member, Stephanie! While coming back from Estes Park, I called up a mutual friend, Stephanie to see if she wanted to meet Gabe and I at Oskar Blues in Lyons for beer and food. Sitting there, Gabe came up with a brilliant idea, why not ‘spice’ things up a bit during the climb? So, Gabe got online and bought a blow-up doll (non-sexual…I think) that we affectionately named, Stephanie. All I’ll say is that she was a HUGE success and quite popular among the climbers. Our team slowly became well-known on the mountain!

The plan was to unload and cook a good dinner and make a carry to 14K-Camp the following day. Since we were all coming from Colorado, we wanted to minimize our time lower on the glacier and make speed for 14K-Camp. No one felt any effects from altitude, which was to be expected but no one wanted to dawdle either.

Speaking of teams, we divided up into two teams of three. We had Team Alpha (Chris, Dan & Gabe) and Team Nacho (Craig, Colin, myself). It was Craig’s idea to start referring to everyone as nachos. Eclecticism does an expedition good with its’ randomness and hilarity. And with Craig, it ran deep. As long as it makes everyone smile, I say go with it. Laughter means better morale.

The carry to 14K-Camp was an easy day although it was extraordinarily windy. A few times at the top of Motorcycle Hill and rounding Windy Corner, we were knocked around, staggering on our feet. I can see how the winds up there can be demoralizing. It’s hard to fight through it. The top of Squirrel Hill consisted of a massive ice flow. Dan and I looked over into the deep gorge on our left and saw a huge avalanche coming off a western gully. Something must have fallen off a small hanging glacier at the top. It was beyond incredible! The power was downright frightening.

Once we reached 14K-Camp, I was floored. 14K-Camp was another town. Compared to 11K-camp, this place was an outright metropolis. When we checked in at NPS headquarters in Talkeetna a few days prior, there were 321 people on the mountain. When we checked out, I believe there were 374. The success rate when we checked in on the 14th was 33%. When we checked out on the 28th, it had risen to 44%, still grim but somewhat par.

The one striking and amusing feature was the pit toilet. It was located directly dead center in the middle of camp, right on ‘Main Street!’ It was absolutely the best view ever from a toilet! You just can’t be bashful or shy about it.

That afternoon, we walked around looking for an empty spot to cache our gear. Somewhat on the perimeter, down a ‘side street,’ we found a suitable empty lot and proceeded to dig a 5’-6’ hole for our equipment. We marked it and walked back down to 11K-Camp and spent that evening eating, drinking and talking to pretty much everyone. It was Monday the 18th and was what I would consider, a particularly good day.

Gabe trudging up the Kahiltna Horn to the summit of Denali. This was around 20,280’. Personally, I had no issues with breathing or low energy levels. I think the excitement took care of all that.

The snow however was weird, making a squeaking sound as we walked.

Tuesday was a day that we were looking forward to. It seemed that once we reached 14K-Camp, we would be within striking distance of the summit. We roped back up with each team taking a sled. The winds were still up to their usual riddles and games. Despite whatever loads one is carrying, the winds pretty much force you to keep moving. It’s one thing if the winds are calm or slightly breezy with single digit temperatures but 30+ mph winds quickly suck the motivation out of you. I can see why some people have said part of the challenge of Denali is overcoming the mental quicksand. Perseverance is the key.

I volunteered to take the sled up Motorcycle Hill. I wasn’t looking forward to it, but I was feeling strong. The one good thing we had this day was that the Korean team whom we had been leap-frogging since we landed on the glacier was a good deal ahead of us. That meant their slow gait would not be a problem for us today.

Coursing up Squirrel Hill, which involved a traverse to gain access to a ramp, I found out exactly what exhaustion was. The footpath was narrow to begin with on what was probably a 35° slope. Even on this mild grade, our sled flipped multiple times along this stretch. Colin, who was tail gunning, was forced to walk 8-10 steps up slope to keep the rope taught and the sled right side up by applying counterforce to the slope. My quads were screaming at me on this segment. It worked for a little while then we lost our cooking board and a sleeve of tent poles! We watched helplessly as they slid all the way down the slope to a small rock fin that guarded the precipice of upper Peter’s Glacier. Talk about demoralizing! We needed those poles. Craig had to untie and walk down and retrieve them since Colin and I were already engaged with the sled. We wanted to belay Craig down, but we couldn’t shift our attentions away from the sled. I took Craig’s coil, Colin shorted the rope between us and we powered the sled up to a shallow depression at the start of the ice flow. Craig was successful and came back with the poles and reported we had lost one. Of course, we had no idea which one. Was it to the North Face Mountain-25 or the Mountain Hardware Trango 4? I had my Mountain Hardware EV-2 (my particular tent of choice) buried at 14K-Camp in the gear cache. So, if things looked grim because of this loss, we still had my 2-man tent to rely on. Craig tied back in and we motored our way to the top of Squirrel Hill and finally to the icy flat stretch between the zenith and Windy Corner.

Halfway across this flat stretch, the back of my legs and butt actually started to contract and go numb. I was reaching my physical threshold. I couldn’t pull any further than a few meters at a time before I had to stop and rest. I was mixing songs seamlessly in my head from Neil Young, Sisters of Mercy (old school Goth), Tom Waits and quotes from Family Guy.

We stopped at an old campsite below Windy Corner and sat for 15-20 minutes. I was done. Colin had to take over for a while from this point on. He & Craig would end up sharing the sled duties for the last mile. While sitting there thinking and staring at absolutely nothing, Craig extended a hammer-gel to me and asked if I wanted it. I stared at it for 10 seconds utterly confused. I couldn’t think straight let alone, find the words I wanted to say. Then I realized what it was. I remember Craig just smiling patiently. I took it, didn’t say anything except that it did taste like apple pie.

The winds were still blowing but it wasn’t all that cold (comparatively speaking). The temperature was hovering around the low teens. Before we set out from 11K-Camp, Squirrel Hill was one of two spots along this segment I wasn’t looking forward to. The other was still coming up, the narrow traverse around Windy Corner. I was hoping, once I regained my composure that it wouldn’t present any problems with pulling the sled…but of course it did.

Colin pulled the sled and Craig was on the end. We successfully managed the climb to Windy Corner, but we had a plethora of people, four different roped teams and three solo people behind us. We caused a bottleneck on the traverse. I was starting to feel better but now Colin was hurting. Craig took the sled and we slowly made our way to a gear cache area at 13,500’ that many people use on the other side of Windy Corner if they don’t want to trek into camp. We elected not to cache here on this trip due to the areas known crevasses and avalanche potential off the higher crags above Windy Corner. It took us a bit over an hour to hike the last .6-mile to 14K-Camp.

This last section can be dicey because the social trail crosses three fairly good-sized crevasses. Considering glaciers are dynamic things, one would think that the snow-bridges would eventually collapse because of the movement. But 14-K camp always remains in the same place. So, I’m assuming there is a large degree of stability here despite the crevasses.

We slowly ambled into 14K-camp like arthritic sloths and collapsed. I broke the news to Chris that we lost a tent-pole. Both tents are labeled as 2-man, but the EV-2 is a tight fit, it's meant for narrow ledges and small spaces. The Mountain-25 has room to spare, albeit heavier. Chris and I preferred the North Face. We inserted one of the poles from my EV-2 and we were fortunate that the pole did in fact, fit. It took a long time leveling the snow, constructing blocks and building up the snow walls of our site. Gabe took to boiling water for food and drinks.

We didn’t do anything the next two days other than rest and acclimate. Between our ‘friend’, Stephanie and the word ‘Nacho’, which had now become synonymous with our expedition name (we carved letters out of the snow and christened our camp, Nacho) we managed to keep a few teams at 14K-camp entertained.

Our closet neighbor at 14K camp was a Russian named Artur Testov and his wife from Juneau (if I remember correctly). He is among a small handful of climbers to summit Denali in winter, January of 1998 to be exact. He also attempted a second summit in January of 2008. I had nothing but mad props for this guy. Forget sports stars and actors/actresses. It’s this type of person whom I respect. When one is sharing camp with people who have climbed above 24,000’ or have climbed all over the globe (China, Pakistan, Switzerland, Russia etc.), it can leave one feeling a bit inferior. Even the Italians (who passed us earlier) were contemplating climbing down the West Rib to the bottom of the Southeast Fork, traversing to the Japanese Couloir and starting the Cassin Ridge. If it were not for the blow-up doll and our ‘Nacho Camp’, I would have felt like a nobody.

While we were resting and acclimating, I noticed all my interactions with people at camp were from places like: Russia, Canada, US, Germany & Korea. We even talked with the medical staff and SAR for a bit about their experiences. Through these interactions, I came to a bit of an unexpected but common-sense conclusion. I surmised that having a sense of humor and great sense of congeniality can work wonders for what is lacking in climbing experience. Group dynamics is huge in expeditions. And just like with workplace relationships, laughter will build friendships and open the door to camaraderie, egos will crumble a little bit and wisdom finds itself being shared by those more experienced.

We ended up meeting two guys, Mark from Anchorage and Thomas from Valdez. We passed them a few days prior on the lower Kahiltna as they were taking a teammate back down to Base Camp who was suffering from AMS. As they were heading down and we were trekking up, we stopped alongside each other and chatted. Mark mentioned that after they dropped off their third teammate, they were going to come back up. I looked at Mark at this moment and respectively said, “Dude, proper!” We both smiled hugely at this. Well, we met up with them again at 14K-camp by happenstance. Gabe, Chris and I were on Main Street talking with random people of which, they were part of (we didn’t realize it then). Then one of them, Mark, made mention that as they were trekking down the glacier, a random guy they stopped next to told them, ‘proper’ when hearing they were coming back up the glacier. He thought that was the coolest thing he’d heard on the mountain. So, I flashed him a HUGE grin, extended my hand and said, “Hi, Mark. I’m Kiefer. It’s a pleasure to ‘properly’ meet you!” We both laughed a long time at this. And for the rest of the trip, Thomas and Mark would be our compliments. Another team, who just happened to be from Boulder, Colorado was also on the glacier: Val, Cindy and Jaroslav. For the remainder of the trip, Val’s team, Thomas, Mark and our group shadowed each other. We all summited the same day and later, the next week, drank together back in Anchorage. In fact, as an example of how small the world can be, one of my favorite places to eat is Nepal’s in Estes Park, Colorado (where I used to live). Near the entrance, they have a TV playing a loop program on Everest, detailing the mountain, explaining the routes, interviews and such. Among the interviewees, was Val at basecamp. Talk about being surprised!

This was also when we met back up with Mark Yoder and John Stasney! Again, as we were standing around drinking hot fluids, acclimating and chatting with people, I heard this God-awful goofy laugh that cut through everything. I looked around and saw someone who resembled Mark Yoder, he had this distinctive nose guard. So, I left my group, walked over to where he was talking with two others and clamped him on the back. “Mark! You old shit. How are ya?!” The laughing fit we all had was epic. They got stuck at 11-K camp due to bad weather and just recently made the move to 14-K camp. I was absolutely stunned to see them again and that with the few hundred people interspersed on the mountain, we would actually cross paths. I took it as a good sign! However, our meeting took a grim tone. Mark and John’s third teammate, Dr. Gerald Myers from Centennial, Colorado whom they met off a climbing wiki-site called, Summitpost.org took off by himself earlier the previous day for the summit. After numerous talks with the medical staff and Search & Rescue, it was believed he was suffering from Cerebral Edema, probably the worst affliction that can strike climbers. Mark and John had no idea why he would just go off on his own (knowing the dangers of being solo and unroped), other than being forced to wait for so long combined with his health deterioration. He hasn’t been seen since and is presumed dead.

“One cannot conceive of grandeur burial than that which mighty mountains bend, crack and shatter to make. Or a nobler tomb than the great upper basin of Denali.”

--Hudson Stuck (Archdeacon, Climber)

Gabe and Washburn’s Thumb

Friday and Saturday, we moved a few things up to 17K-camp (high camp). This was the highest Gabe had ever been. He was able to set a personal record. Unfortunately, we found out the previous day that Colin wasn’t feeling good. It had been nearly 4-5 days since Colin did feel well. The culprit was digestive and intestinal problems more than likely due to AMS. Anyone can come down with AMS with symptoms ranging from simple headaches to debilitating mental confusion. It generally occurs above 8,000’ and effects around 200,000 people each year. And for whatever reason, younger people are more susceptible. Roughly 30% of the climbers attempting Denali are affected by this condition. I’ve read some medical corollaries about the connection between acclimatization and altitude and some peoples’ seemingly natural adaptiveness to it. Some papers try to explain it via physiology and genetics (think Ed Viesturs). But that doesn’t explain why some can go above 6.000 meters (19,680’) on South American peaks and then get stopped above 4.500 meters (14,760’) in Canada or Alaska. I know there is a strong correlation of slow acclimatization and altitude tolerance. But I’m intrigued why that doesn’t apply to everyone. Myself for example, I was practically jogging up Pico de Orizaba on an acclimation hike to 4.600m (15,200’) and had no problems on Denali. Yet my Asthma as a kid nearly crippled me. I personally find the science and physiology of altitude fascinating. Knowing Colin had summited big peaks (Cotopaxi, Chimborazo) in South America and watching him now struggle was saddening.

The six of us started up the 35° snow slope towards the fixed ropes. We stopped at the bottom of the lines and saw Colin stop far below us. We watched him sit down, rest for what had to be 10-15 minutes and finally turn around. We debated among ourselves and concluded that he simply needed another day or two to acclimate and hydrate. If it came down to it, one of us would hike back down with him and see him off back at the airstrip. It was something we’d address and talk about once we got back down.

This was my first time on fixed lines. So, with a little direction from Chris, we were off. Getting up over the bergschrund (15,400’) was a bit tricky. Placing the ascender as far up the line as was possible (given the length of the cordalette attached from the ascender to our harnesses) with the left hand, cocking the left foot up on a hold almost waist level and swinging the axe into the ice with the right, I mini-jumped, pulled myself to a pseudo-standing position and finished by swinging my left foot over to another hold, sliding the ascender up further, re-swung the axe higher & pulled myself up to a more level place and continued up the line. The second time went smoother once you got the hang of it.

The low to mid 50° ice headwall took a bit of time to get up because of other climbers and us figuring out this whole ascender thing. But once we reached the ridge (16,200’), the views erased all our frustrations. We were well above the clouds. It reminded me of the way the clouds moved in and banked up against the coastline a few years ago on Tenerife (Canary Islands) while climbing Teide and some other smaller peaks near Puerto de la Cruz.

There was quite a crowd on the ridge and amazingly, there were the Koreans taking a smoke break, at 16,000+ feet. It was like watching an elephant choke on a peanut…just incredible.

We made it to High Camp, dug a passable cache and wasted no time in getting out of there. It was cold, exceptionally windy and just generally unpleasant. The wind chill was stinging.

The descent of the fixed lines was straightforward and easier than I was expecting. This was done by allowing a partial arm rappel backed up with a safety tied to the harness and clipped at every anchor. I used a short quickdraw for this doubled with two carabineers. This allowed for an easy ‘walk-down’ just so long as one kept their momentum under control.

We spent the remaining day drinking and talking (among ourselves and with our neighbors), discussing Colin’s situation and relaxing. From the short time we spent at 17K-camp, I just couldn’t shake the cold from my bones. I stayed cold for the rest of the day despite walking around drinking hot fluids. I went to bed early hoping to find warmth via my two sleeping pads and -20° bag; fortunately, it worked.

Unfortunately, the next day, Saturday, Colin still wasn’t feeling any better and he didn’t look any better. We stayed in camp taking another acclimation day. Colin, as much as he wanted one of us to accompany him down, didn’t press it. He found two Mexicans who were heading down, one of whom was a physician and since they spoke English and Colin a little Spanish, he was comfortable with this decision. Later that afternoon, Colin decided to descend; things would have only gotten worse anyway.

We woke early the next morning, sometime around 7:30 am. It was cold! It was one of the few days where we did set an alarm. Our team didn’t exactly set any speed records on breaking camp on this expedition. From the horde of people ascending the ice wall the previous day, we knew we’d have to get up early & get to the fixed lines before the barrage of other climbers did the same. Upon getting ready to set out, we noticed Thomas and Mark were already halfway up the slope.

Saturday, we tallied at least 72 on a single count, it looked like a scene out of the old black & white footage from the Gold Rush of everyone heading up Chilkoot Pass. With the forecast being favorable for Monday and possibly Tuesday, everyone was just setting themselves in position for a summit bid, us included. We had dug out one of our buried ropes from atop the West Buttress and continued moving towards Washburn’s Thumb (rock feature). When we reached High Camp, what we had found was that the ghost town from Friday had blossomed into a slow dance of tightly wrapped but brilliantly colored ants building shelters.

All the available tent platforms had already been taken. We were forced to level two new spots, saw chunks of snow/ice and build our own walls around the tents. This was an absolutely tiring and laborious process. The lack of oxygen and air pressure was noticeable. But we were able to meet up again with Val, Jaroslav, Cindy, Mark and Thomas. Having friendly faces like that really does positive things for one’s motivation. Plus, I would be lying if I didn’t say there was a small but tangible facet of friendly, non-team competition.

The weather window according to the nightly NPS reports was looking to be Monday and Tuesday for summit days. A massive low pressure was moving into the area late Tuesday night and would last for the next 4-5 days dumping 8” and more of snow and scouring High Camp with 70 mph winds and 14K-Camp with 40-45 mph winds.

As we roused ourselves Monday (Memorial Day), we didn’t bother joining in the chaos of High Camp that morning due to three reasons. One, we wanted to wait for the winds to die down as Chris and I had noticed. This seemed to be the norm in the mornings (the snow devils and spindrift coming off Denali Pass and the upper ridge were massive). Two, we had no interest in joining the ‘congo-line’ of people heading up the ‘Autobahn’ towards Denali Pass and lastly, we were all running low on water.

Due to the dry quality of the snow, it took almost three hours to melt enough snow for everybody. We did, however, keep our preparations going for our summit departure and at 1:00 pm, we set out for Denali Pass.

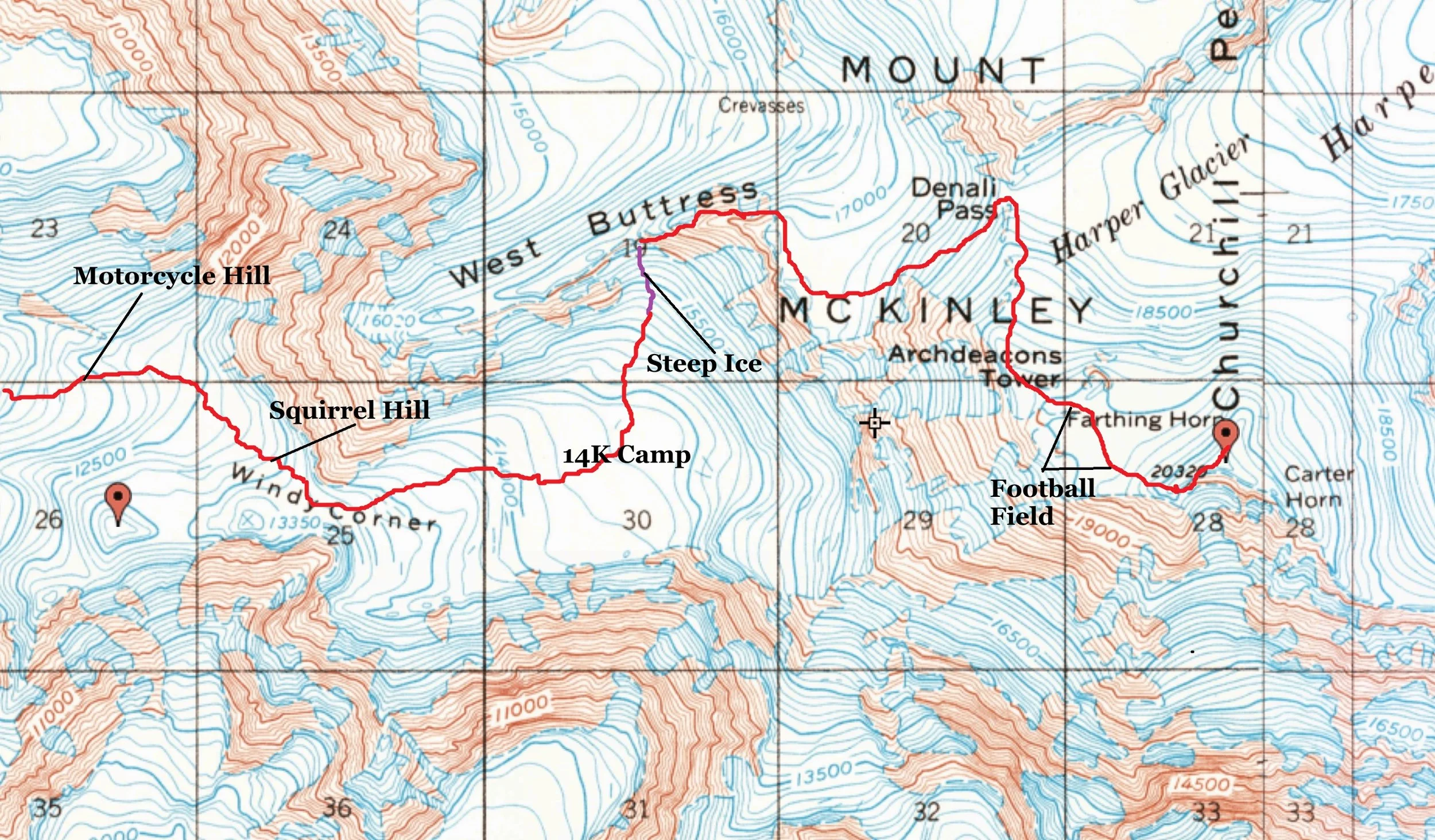

Between High Camp (17,200’) and Denali Pass (18,300’), there is a moderately steep traverse known as the ‘Autobahn’. It is anchored for running belays (pickets) and at busy times, it’s prudent to use them.

Some of the most dangerous and reckless behavior I’ve seen has occurred along this stretch on the way down. People roped up mind you would traverse this section with nothing more than a pair of trekking or ski poles. I’ve never heard of a pair of trekking poles stopping or arresting one’s fall needless to say, the rest of a team. I had a good friend back in Colorado do this coming off a Fourteener, showing off to his partner die from his sustained injuries.

We ended up getting stopped at Denali Pass for about an hour with four others waiting for the wind to die down. This is where Dan came to the sad conclusion that he couldn’t continue due to his feet swelling. A few of his toes were also starting to go numb. Being the EMT of the group, no one questioned his decision and coming so far, it was a decision that was hard to make if not admirable.

People were turning back and heading down the slope while we were waiting there. Two members of a group that we were sitting next to, tied into our rope with Dan and proceeded back to 17K-Camp. Gabe, Chris, Craig and I covered all our exposed skin and pushed on around the pass into the wind hoping for a reprieve.

The people walking down the ‘path’ were mixed between those who turned around because of the wind and those who had successfully summited. What we found out was that the further away from the pass we climbed, the wind lessened little by little. By the time we reached a few hundred feet below Archdeacon’s Tower (another rock feature), the wind had almost completely abated; a lesson and prime example of the Venturi effect.

The route from Denali Pass to the Football Field (19,500’) went smoothly and was as straightforward as they come. At the leading edge of the Football Field, we untied from the rope, stashed it with our packs and continued in detail. However, all morning, I hadn’t been feeling ‘myself’. I was slower than everyone else and lagged all day. I left the group, told Craig to continue and that I’d catch up in a little bit. I wondered off from the trail and dug myself a cathole to perform some ‘business’ in relative privacy. The dehydrated food I had the previous night hadn’t digested (Mountain House Pad Thai Chicken). I only make mention of this because it seemed, in hindsight, small meals and snacking are of more benefit to your body then ‘loading up’. Digestion at high-altitude is inefficient.

Looking up at Pig Hill from the Football Field was a bit disheartening. We knew Pig Hill topped out at a little over 20,000’ on a feature called the Kahiltna Horn and I have to say, this last hill just made you shake your head in disbelief. It is arguably the hardest section past High Camp due of course, to the altitude.

Craig Berger on the ice headwall

Myself back in Talkeetna marveling at how much weight I had lost!

Reflections in my glacier goggles. Mt. Foraker in the background.

Resting at Camp-3

Gathering our gear at the TAT bunkhouse

I slowly pulled away from my teammates and eventually passed two Brits ascending Pig Hill. It’s unfathomable that LaVoy, Browne and Professor Parker made it to ~20,250’ wearing multiple layers of wool, leather and fur and were turned around due to an increasing blizzard back in 1912. I don’t know if the men of bygone days had more ‘grit’ and ‘tack’ or if advances in clothing & technology have allowed current explorers to achieve more with less. I couldn’t imagine being at 20,000’ or more wearing clothing like cotton and leather that would stiffen more in cold temperatures.

The summit ridge is NO PLACE you want to be in high winds. It is exposed, narrow, corniced in a few spots and as Chris pointed out, hollow by the sound our points made in a few areas. We could wiggle our front points in the snow and get a squeaky sound to emanate. The summit ridge is a very aesthetic and beautiful line. Back down on Pig Hill, I didn’t believe Thomas’ opinion of the ridge when he said,

“From the horn, it’s all gravy!”

But it wasn’t bad. Along this stretch, Gabe and I pulled away from the others. My emotions got a hold of me for a minute near the summit and I did tear up. A quote from Hudson Stuck's novel, "The Ascent of Denali" (1914) has stayed with me and made an entrance in my head as I was standing there looking at The Moose’s Tooth in the distance,

“The view from the top of Mt McKinley is like looking out the windows of heaven”

--Robert Tatum, 1913

…Indeed.

And I can understand why he said this. After laboring for 13 days or more on a singular goal, looking down on the multitude of peaks, some climbed, some unnamed, witnessing the boulevards and terraces of wadi ice first-hand, hanging glaciers & seracs poised to unleash a maelstrom of violence, it all hits you simultaneously.

Craig and Chris came strolling onto the broad summit and joined the rest of us. We shared it with some familiar faces; Val and Jaroslav were also there as was a lone person from Poland, one guy from Mallorca and eventually, the two Brits reached the precipice as well, a very long and tiring way from Manchester as it happened to be.

We reached the summit at 8:50 pm. It was ours for a solid 30 minutes before reason took over and gave us the nod to get moving. We put the summit temperature to be around 5° to -5°, unusually warm.

The descent went surprisingly fast. I was in my own little world. The scenery passed by without notice. From Pig Hill looking out west, the ponds and lakes on the distant tundra looked like shiny, golden coins from the sunset. For whatever reason, I thought of safe passage for the dead.

I eventually passed Gabe and sped down the Autobahn passing a few others anxious to get back to camp. Walking along this section at 11:30 pm, still buzzing from standing on the summit, the entire slope glowed orange and red from the sunset. It almost appeared to be glowing from within. It was surreal and something I hope to experience again before I die.

Dan was ready with fresh water and a thermos of hot water. I greedily drank a cup of hot water, munched on some gorp, shed my layers of clothing and hopped in the tent. I passed away into sleep just as the others were coming into camp…

“But tonight, the lion of contentment has placed a warm, heavy paw upon my chest.”

--Billy Collins

Knowing that some serious weather was moving in, everyone was anxious to get down as fast as possible. It felt like we had cheated the mountain in terms of having great weather. Our experience with Denali’s infamous weather had thus far been very atypical. Being stuck at 17K-Camp or even 14K-Camp was not on the agenda. Although true to form, we woke somewhat at leisure Tuesday morning and even though we again, didn’t set any speed records breaking camp, we moved with solid purpose. Though now, Craig wasn’t feeling well. The previous summit day had seriously tapped his energy reserves. He had to dig deep to keep going and because of reaching his threshold, I think this enhanced a bit of AMS.

Craig would not be his normal self until the morning of the 28th. By the time we had reached 14K-Camp, it had started to snow lightly. We immediately proceeded to dig up our cache. Now we had a predicament on our hands. There were five of us but enough gear and food for six. Plus, the food we had would last for another 9 days! We planned on summiting with six people and spending more time on the mountain then we had. We had to get rid of the extra food. Dan and I loaded up one of the sleds and pulled it around camp announcing free food, a common practice. We probably gave away close to 80% of what we had. Though I’m sure having that storm roll up in the next day probably helped.

To prove further what a small world it really is, before we left for Alaska, Chris and I had received an e-mail from a guy named Matt who works for Corporate Vail Resorts in Broomfield. Through a small network of friends that include Barry and Donna Reese (who forwarded our e-mails to each other), there might be a chance we’d run into each other since we’d be on the mountain at essentially the same time. After all, stranger things have happened.

To cut to the chase, while Dan and I were giving away food, I lingered around this one group in particular talking to one of the guys. After 10 minutes or so, we exchanged names, looked at each other suspiciously and smiled.

“Matt! How the hell are ya!?”

What are the odds of running into someone you’ve only e-mailed and have never met? Let alone on a mountain a few thousand miles away? It was absolutely amazing. So, we stayed and talked for another 15-20 minutes until I got called back to lend a hand in packing.

But it gets better. A friend of mine who works at Bag & Pack in Avon, Co. told me a co-worker of his named, Ron was also planning on being on Denali a short while after us. I talked to this guy on the phone a couple of times, but we couldn’t get any training climbs coordinated. While continuing to give away food, I kept talking to this one guy because he seemed pretty cool. I got a good vibe off him. Eventually I asked him where he was from,

“I live & work in Avon, Colorado.” He said while cutting snow blocks.

I looked at him in a scrutinizing manner for a few seconds, said nothing, then,

“Ron!” Then he stopped what he was doing and looked at me with a shocked expression,

“Kiefer?” Then of course, we had to start another ‘sewing circle’. I think my teammates were getting annoyed with me that I wasn’t helping much in packing.

I swear once I can see but twice? That almost goes way beyond coincidence. We packed up everything and headed out for 11K-Camp. And wouldn’t you know it. Once we reached Motorcycle Hill, guess what? We got stuck behind our good Korean friends again! I mean seriously, how does that happen? I never did find out if they had summited. What a wild and surreal day.

Upon waking the next morning, we woke to fresh snow, winds and some cold temperatures. The clouds had blotted out most of the surrounding features at camp.

We picked up a guy named Greg at 11K-Camp as we were planning to leave. He was a guide with one of the companies looking for a rope to tag onto. He needed to get back down to Base Camp. The whiteout down the glacier lasted the entire length. The only reason we made it back to Base Camp this day was because of Chris’ GPS. If we didn’t have it, we’d be spending another night on the glacier. The whiteout was disorientating and complete. I had similar conditions on Snowmass Mountain back in March but nothing this complete. To drive home the confusing atmosphere further, somewhere below Camp-1, we astonishingly ran into the Korean team again (seriously!).

They too were heading back to Base Camp…only they were moving UP the glacier back to Camp-1. They had NO IDEA of where they were. With the crevasses on the lower glacier, this was a bad place to get lost. We post holed a few areas a lot deeper than what was comfortable. I held my breath more than a few times. Looking back, we had a regular ‘conga-line’ of people following behind us, including Val and Cindy who tagged along! In total, I believe we had 17 people in our line.

But we did eventually make 7,200’ Base Camp again. I checked back in with Lisa, set up camp (ALL of us next to each other), and we celebrated with lots of beer and schnapps and hoped that the weather would cooperate for a departure the following day. No including what the others had brought, our team had about four cases of beer and a couple handles of vodka. And since we all gathered underneath a giant ‘mega-mid’ that Val’s team brought, we all spent the next 48 hours in perpetual drunk company. Because of the beard that Gabe had grown out over the prior two months, he looked like Santa Claus on a bender! From start to end, after a total of 14 days on the mountain, 11 emaciated pounds lighter (personally) and a noticeable difference in my belt size, our McKinley expedition had reached its end.

Denali illustrated the importance of proper planning and how important teamwork is. One must understand that people are not going to get along all the time for whatever reason. Some people are naturally drawn to introspection (I’m one of them) and some are quite vocal about their frustrations. The ability and talent in a good, solid climbing partner is being able to reign in those frustrations and let them out to breathe only when necessary. But the other side of that is being able to listen, take advice even when not needed and use it constructively. A good partner is humble when he doesn’t need to be. A good partner knows when to stand up, take charge and when to lay low and allow himself to be led. Group dynamics is the key. Such things take effort and won’t come easily.

*Chris Pruchnic died on November 20th, 2010 while climbing a mixed route (“All Mixed Up”) on

Thatchtop Mountain, a peak in Rocky Mountain National Park. I just happened to be up on Longs Peak that same day.

Chris was a solid guy. I miss you buddy.

The plane reflected in my glasses back at base camp.

Chris Pruchnic nearing the top of the West Ridge

The Football Field

Myself approaching the ice headwall. 14-K camp below.

Climbers stopped just below Denali Pass (including us).