Mount Wilson

14,256’

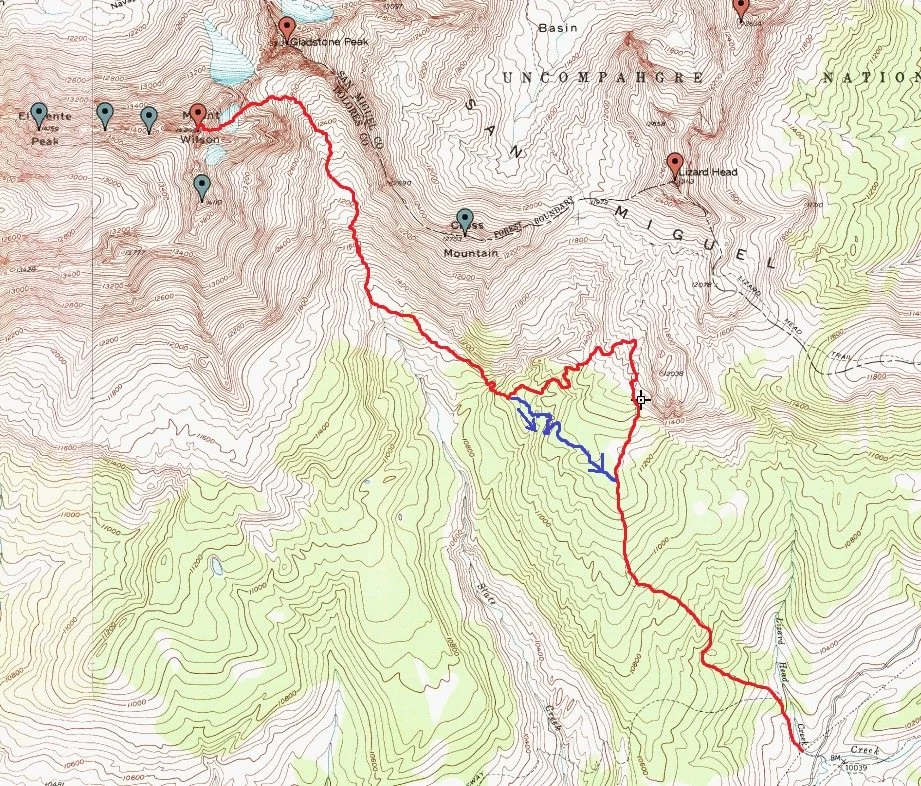

16.1 hours / 14.3 miles / 5,697’ gain

For the times I’ve been out and about, even with a low snowpack this year, overall conditions have seemed pretty tough. A buddy of mine even got turned around on Mt. Adams recently. For the price of NOT having to wallow, wallomp and wail in the trees, the alpine dues seem higher.

Prakash and I left the Cross Mountain Trailhead at 3:10 am under clear skies and 18°. There were already six vehicles in the small parking lot. Cross Mountain gets heavily used by cross-country, Nordic skiers & snowshoers. In winter, Lizard Head Pass is a popular place for snowmobilers and skiers. I’ve skied (Nordic) the pass multiple times as the local ski club grooms it down to Trout Lake. The existing path was heavily used and well-packed. You could have run this in trail-runners with microspikes and been fine.

This small, 41,000-acre Wilderness was named for the lizard-like spire back in the early 1930’s. The Forest Service added Mt. Wilson and Wilson Peak in 1932 to this designated primitive area for protection. But it wasn’t until 1980 when the ‘wilderness’ designation was bestowed, permanently protecting this area. Bill Middlebrook has a good section on the historical naming aspects on Mt. Wilson over at 14ers.com. Check it out!

This was my second attempt at Mt. Wilson in winter. My first, back on January 25th, 2020 saw me giving up the ghost a few hundred feet from the summit because the snow conditions went from great to horribly dangerous. So, at that point, wearing a beacon would only result in a popsicle recovery come spring. Although, I will say, on that attempt, I dug out a fantastic campsite complete with shelving and seats. Even the top of the tent was below snowline. Now, you’d be lucky to get your ski pole down past a foot before hitting rock/grass.

We admittedly got lost in the forest. To my knowledge, there is no “official” winter route. From what I’ve learned on these two trips, the least painful way to get in/out of Slate Creek, is to look at prior trips and plan your approach by way of GPS and a topo map. Staying out of Slate Creek proper and closer to Cross Mountain is key.

We traversed into Slate Creek staying high along the northern (right) edge. We ended up hitting treeline around dawn. In the summer, there’s a bench at this point that would make for some pretty good camping. The alpenglow bouncing off Gladstone and South Wilson was spectacular. Sometimes, I think the early mornings and cold travels are worth it for those precious few minutes of orange splendor.

Gladstone Peak

The snow was acting reasonably well; icy crust from the cold twilight and thus, supportive. We cruised up into the basin at a slow but steady pace. No need to race when we had all day. Even with the time lost playing around in the dark in the lower forest, we were still doing good on time. However, the traverse to El Diente which, was still on the table, was looking less likely. Temperatures were hovering in the low-20°s with the occasional arctic gust sandblasting us with icy grit. So, cold enough to keep you moving.

There are three minor hills one must ascend to achieve the upper basin. And even then, you won’t see Mt. Wilson or the seldom climbed/skied Boxcar Couloir until the 90° dogleg near the East Face of Gladstone Peak which, is imposing as all hell.

My old climbing buddy, Aaron Ihinger has mentioned to me there’s a C3 route up Gladstone Peak from the saddle with Mt. Wilson. And having studied this part of the ridge a couple times, I still can’t see anything that wouldn’t involve rope and high consequence. So, I don’t know.

The icy wind gusts, pouring down on us from on high, were now more frequent as we rounded the corner and could now, look up into the couloir still a few hundred feet above us. We found a good pile of chocolate chips and decided to abandon our snowshoes at this point. Piling them with rocks that we chopped from the frozen talus, we secured them and started the ascent up the East Face.

Prakash led out first. I stayed behind a bit to put on crampons and steal a few swigs of Gatorade. He was really cruising up the snow and exposed talus. It took me a while to catch up with him despite taking a more direct line up the snow. Looking off to the left, I could see the exit to Boxcar Couloir start to come into view. It’s a relatively flat plateau and offers a good place to break. Above that, there’s a large outcrop of rock poking out of the snow like a bunion. That was my high-mark from last time. I cruised past this feature slowly grinning as I was starting to think we might actually get this bugger!

I eventually overtook Prakash by taking a more direct line up but also, miraculously, he still hadn’t put on crampons! I tried following some old tracks but honestly, even they didn’t help much as the whole slope was pretty damn firm.

I slowed down to kick steps for Prakash to ease his climb. We were high enough, that there was no safe place for him to stop and suit up! (to quote Barney from, ‘How I met your mother’). The snow was so hard, I couldn’t even plunge my axe into the slope. I resorted to using the pick. Even 3-4 hard front kicks only resulted in a half inch of penetration. And unbelievably, it wasn’t ice. I found climbing ‘duck’ and using the inside points seemed to work better. And since I naturally walk duck-style anyway, I was very comfortable with technique. Impressively, Prakash seemed to be doing just fine! I explored the coully a little bit by weaving back & forth looking for softer snow but never really found any.

Myself resting before climbing to the ridge

I aimed for the right rock wall knowing the snow there would be softer. When I reached the palisade, I managed to stomp out a platform in the moat that felt fairly stable. After giving my calf’s a few minutes to rest, I continued up, traversing back into the center of the couloir. Prakash arrived at the platform 5 minutes later and strapped up.

Roughly 30’ from the top of the col, the snow immediately went to thigh-deep unsupportive powder. As rigorous as trenching up a 42° slope can be, today, I’ll take it over the compacted, “slip & snow” from below. If you can’t even plunge an axe into the slope, it’s time for a second tool (which I didn’t have). I reached the col, found a small, exposed rock in an alcove to sit on and waited for Prakash to arrive not wanting to get too far separated.

Honestly, I was miserably cold sitting there. I had every article of clothing on I had brought, and still, the winds were doing their worst in evaporating my warmth & enjoyment. But the redeeming part, and sometimes you have to remind yourself of this when the elements are battering & lashing you like a storm-driven ship, is that I was sitting in a spot that one could easily see in an article of Alpinist Magazine or in a movie. And knowing that, actually makes dealing with the miserable…manageable. And there is a small amount of pride one can take away knowing that. I honestly think, the mental game is tougher than the physical.

Prakash arrived after a few minutes and we climbed an additional 15’ up the rock to a small perch. We could see the summit only 30’ above us guarded by some tricky vertebrae of stone. We shed our crampons and investigated how to get around the first small block. Venturing out onto the faces would have been quite the proposition not knowing if there were small footholds under the snow or slab. After a solid 5 minutes, Prakash found the key to unlock this problem. A couple full arm wedges and a knee inside a large crack, followed by bear-hugging a horn, finally allowed us entry onto the summit! And damn was it windy! But we did it. And the snowy landscapes afforded to us were well worth it. The view of the traverse to El Diente alone was worth price of admission. But due to time, the traverse wasn’t in the cards for today. Guess they’ll be a Kilpacker Basin trip on the horizon soon.

Climbing down the spine of the granite redoubt was easier than on the way up. probably because we knew the moves. Even climbing down the couloir went way faster than I would have thought. I usually try to plunge-step everything when I can, but the snow was just too hard to do this safely. And it was snow; there was no ice. So even if I could have gotten my axe in, I’d worry about cracks opening up and sliding.

SUMMIT!!

Once we were back in the talus at our snowshoe cache, we high-fived each other and whooped loudly. We sped out of there as fast as we could wanting to take advantage of all the remaining daylight. And it worked. We retraced our tracks from earlier to speed things along. At the right moment, we left the comfort of our track and headed into the untrammeled snow of the forest, bee-lining it for the packed Cross Mountain Trail where we arrived just as dusk was devouring the last of the light.

I have to say, climbing some of these harder “frozen fourteeners” can be a real challenge as it forces one to slow down and make more nuanced decisions. Even individual footfalls can change the outcome of the next moment if made imprudently or recklessly. But honestly, that’s where the real outdoor education comes from. And despite this being a depressingly low-snow year, the snow conditions that do exist, have been more challenging then when the snowpack is deep and fat. This winter season seems to be more about finesse and less about grunt-work.

Myself on the summit enjoying the World-class views

Gladstone Peak as viewed from the summit of Mt. Wilson to the south. At 13,923’, it is among Colorado’s top-100 highest peaks.

While not the hardest peak to scramble or climb, it offers some of the best views of the Wilson’s and the peaks around Lizard Head Pass.

There are two main routes to the summit. The notoriously loose North Ridge as it connects with Wilson Peak, and the lesser-climbed East Face.

Boxcar Couloir